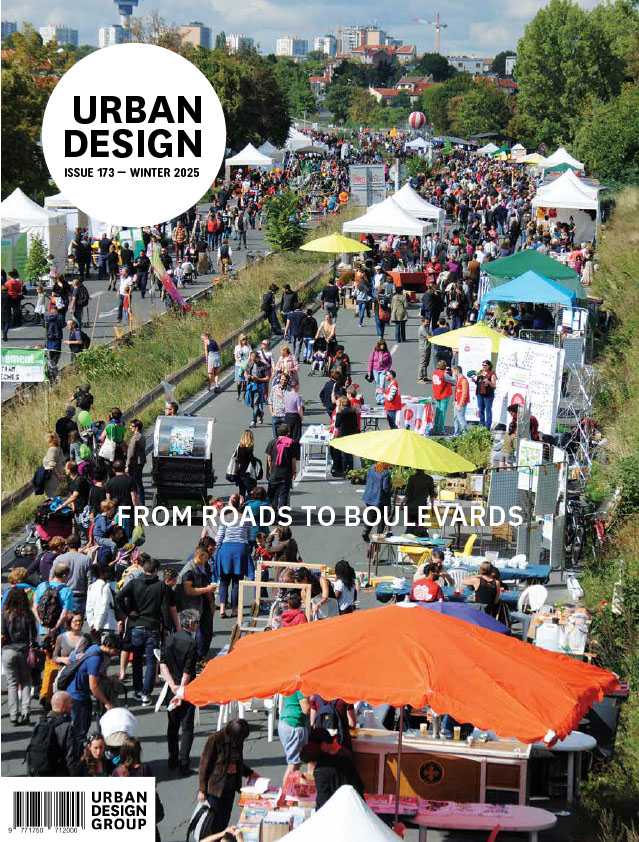

Guest topic editor Paul Lecroart introduces the work underway across Europe to turn highways into green streets. The following articles illustrate the story of eight metropolitan cities engaged in the challenging process of transforming large pieces of road infrastructure and their urban hinterlands.

While some cities follow a pragmatic approach with one-off projects, others such as Barcelona, Birmingham, Brussels, Helsinki and to some extent Paris envision highway-to-boulevard corridor conversions as a structural component of their urban strategies, finding their way into city or metropolitan-wide master plans. Removing the barriers to urban intensification is the driver of highway changes in both central areas (Birmingham and Wroclaw) and along radial road corridors in the city fringe (Brussels and Gothenburg) or suburbia (Barcelona). The need to re-allocate road space for a new tramway line provides a strong lever for converting expressways into street level boulevards in Helsinki, Gothenburg and the Paris Region. Where alternative streets exist or can be created, segregated roadways are being closed to traffic and given back to the public, as in the successful pedestrianisation of the Paris River Bank Expressway.

Recycling segregated highway networks into green, walkable and cycle-friendly streets, with the support of socially equitable urban redevelopment and transport demand management policies, is increasingly becoming a way of adapting cities to social and climaterelated challenges. Highway strategies can be highly transformative for cities and regions. They can stimulate mixed use, polycentric, walkable and heathier urban environments for all. They also force traffic to evaporate, encouraging a shift to less car travel and car-less living patterns. However, systemic change is challenging for public bodies, citizens and businesses, as it can create conflicts with short-term interests. It requires an open-minded, collaborative, participative approach with a high degree of political co-operation between national, regional and city governments. Incremental change can help to build community support with small steps paving the way for bigger change. A combination of strategic long-term thinking, a desirable win-win narrative, and the implementation of cheap, people-friendly, tactical actions can be a great help. However, there is an obvious need to rethink current planning paradigms, instruments and funding streams to meet the fast-changing challenges of the 21st century.