Since 2010 the Paris Region has been engaged in an unprecedented development cycle stimulated by ambitious and innovative projects in a wide range of sectors. Space is being increasingly used up, pressuring transport systems, with social and regional disparities rising. Despite fragmented governance, the ambitions of the key players of the (Wider) Grand Paris are metropolitan in scope. Decisions for 2030 have mostly been taken, but what about 2050?

Paris is first a natural setting that has developed into a capital city: spanned by an axis crossing the Île de la Cité and connecting Mediterranean Europe to Flanders, the Seine has formed a large river basin. Urban growth began in this hollow, creeping outwards towards the Plaine de France and the surrounding valleys before climbing up to the plateaux beyond.The Seine remains, more than ever, the Grand Avenue of Grand Paris—and is somewhat neglected in places. The geography creates a natural and manmade landscape structure that runs northwest to southeast: the historic axis from the Louvre to the Grande Arche, the Plain of Versailles, etc. This geo-historical structure shaped the 1965 Regional Master Plan, determined the location of La Défense and the new towns, and led to the layout of the suburban rail network (RER). But other processes were also at work: the radioconcentric growth of Paris as it overflowed its defensive walls, the industrialisation and parcelling of the suburbs alongside the railways during the nineteenth century, the major post-WWII urban developments, and the more diffuse urbanisation of the 1980s.

Urban regeneration and the metropolitan awakening

From the 1990s onwards, the regeneration of deindustrialised areas took over from urban expansion, and the centre attracted renewed attention. This dynamic was stimulated by a new generation of mayors who had cut their teeth during the decentralisation period, many of whom understood the importance of collective action: this was the case for the rebirth of the Plaine Saint-Denis which began in 1985, of the Renault plant in the 1990s, and of the Vallée Scientifique de la Bièvre, after 1997. In 2002-2007, public planning bodies were set up to manage the transformation of “Strategic Areas”: Seine- Arche, Plaine de France, Seine-Aval, and Orly- Rungis–Seine-Amont. Some had the status of opérations d’intérêt national (OIN: key projects of national interest), all were supported both by the State and the Île-de-France/Paris Region Regional Council. As a major driver of regional development, the Regional Council assumed new responsibilities from 1995 onwards: both as the public transport authority with Île-de-France Mobilités, and for planning, via the revised Regional Master Plan (SDRIF). A blueprint for the new Plan was approved in 2008. As President of the Republic from 2007, Nicolas Sarkozy opposed this blueprint, which he felt lacked ambition. He appointed a Secretary of State for the Capital Region and in 2009 launched his “Grand Pari(s)1”: an international call for ideas focusing on the future of Paris Region. This further raised awareness of metropolitan issues, which had been fuelled in 2001 by cooperation initiatives supported by the Mayor of Paris, Bertrand Delanoë: bilateral agreements with neighbouring towns, the Conférence métropolitaine in 2006, and the creation of the Paris Métropole consultative organisation in 20092.

Grand Paris and Île-de-France 2030: a marriage of reason

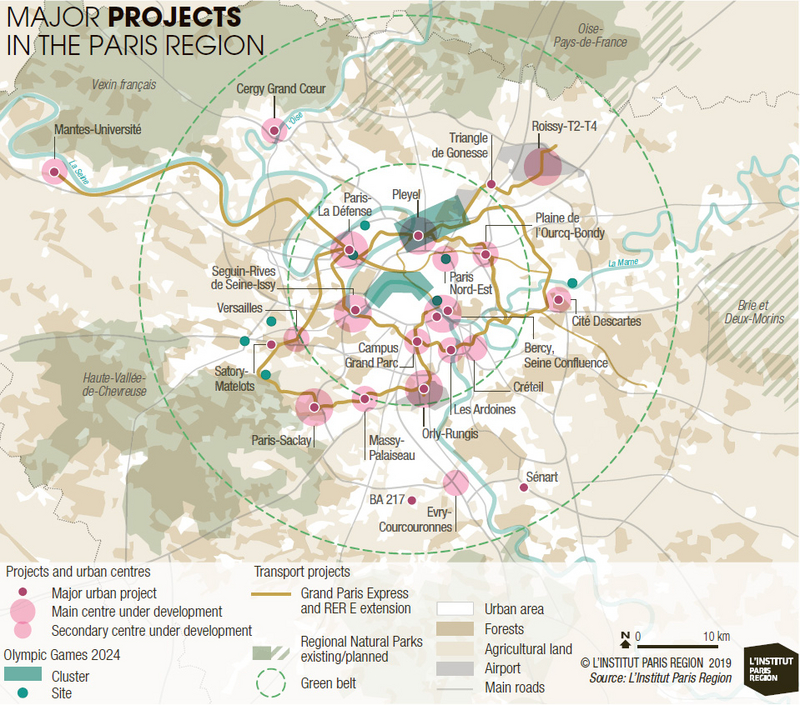

An act of parliament on Grand Paris was passed in 2010. It created two tools: a public body for the Plateau de Saclay key project, and most importantly the “Société du Grand Paris” tasked with designing and building the ambitious Grand Paris transport network. Nicknamed “le grand huit”3, this project for a rapid metro system designed to connect suburban economic hubs (Roissy, Orly, Saclay, La Défense, Cité Descartes) stood as the alternative to the “Arc Express” project mooted by the Regional Council, whose aim was to serve densely populated areas in the immediate suburbs. Both drew inspiration from the Orbitale network, which was proposed in 1990 by IAU (now L’Institut Paris Region) and included in the 1994 Master Plan, but was then shelved for financial reasons. Following a public debate in 2011, an agreement was signed between the government and the Regional Council combining the two projects and launching the “Grand Paris Express”. This was enshrined in the Île-de-France 2030 Master Plan, which was finally approved in 2013, providing the regulatory framework for inter-regional planning initiatives. The Plan confirmed the principle of a “compact polycentric metropolitan region” and set goals for urban densification and the construction of priority housing around railway stations. By emphasising regional socio-economic balance and environmental transition, Île-de-France 2030 anticipated the new post-Quito global agenda of 2016. Its implementation nonetheless relies on political visions that have since changed.

Grand Paris Express, the 2024 Olympics, RER E: transformative megaprojects?

The planned Grand Paris Express is a driverless metro 200 kilometres long with 68 stations, made up of four new lines (15, 16, 17 and 18) and an extension to line 14. The idea is to interconnect the current radial network, which is centred on Paris, in order to facilitate inter-suburban journeys. Introduced gradually between 2021 and 2030, it should de-saturate the existing lines, offer an alternative to car use, and foster the development of dense, mixed-use urban centres. As the future intersection of five metro lines and the RER D, Saint-Denis-Pleyel will become a hub of Grand Paris for the twenty-first century. As the heart of the 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games, it will receive a powerful boost thanks to the riverside athletes’ village, the water sports centre opposite the Stade de France and, a mere javelin’s throw away, the Le Bourget-Dugny media village. Initially encouraged by the state through regional development contracts, local authorities in the zone of influence of the 68 stations are vying with each other with projects for housing, facilities and offices4. The Grand Paris Express will be able to play its part as a “transformer” of metropolitan space all the more effectively if it comes in on schedule (anticipated costs have risen from 25 to 35 billion euros in 5 years), if it interconnects with the existing network, and if the urban development projects form part of a shared, coordinated strategy. Other issues remain, however: the examples of Tokyo, Berlin and other cities show that the “network effect” is much more powerful when ring metro systems run in continuous loops with no disconnections. Some surburbs of Paris will also have to be better connected to the network. Another major developmental event will be the completion in 2022-2024 of the east-west RER E regional rail link between Mantes/Poissy and Chelles/Tournan, forming a development axis between the hubs of Nanterre-La Défense, Porte Maillot, St-Lazare, Magenta (the Gare du Nord 2024 project), Paris Nord-Est, Plaine de l’Ourcq and Val-de-Fontenay. With the extension of four metro lines, 10 standard and express tramways, and by 2025 the construction of the CDG Express rail shuttle to Charles de Gaulle Airport, a revolution is afoot in the Paris region transport system. It should be combined with a new regional mobility strategy for 2030-2040, as the urban transport plan (PDU) expires in 2020.

Building 70,000 homes per year...

The players of Grand Paris are also pushing to kick-start production of housing. In the 2000s, the 35,000 units built annually in the Île-de- France Region were insufficient to respond to real needs: the government included the goal of doubling this figure in the Grand Paris act of 2010. After a decade of efforts by the entire stakeholder chain, targets have been reached with work on almost 80,000 homes beginning in 20185! However, real growth in the housing sector is limited by the number of homes that are demolished or restructured6. Urban renewal programmes across the Region ushered in an exceptionally large number of renovation projects for high-rise social housing estates: between 2003 and 2015, 37,000 flats were demolished and reconstructed, and 84,000 were renovated. Areas where housing is being produced do not map precisely onto dynamic areas with buoyant job markets. This means that 2/3 of new housing is built in the outer suburbs, increasing the need to commute.

Assets, weaknesses and governance

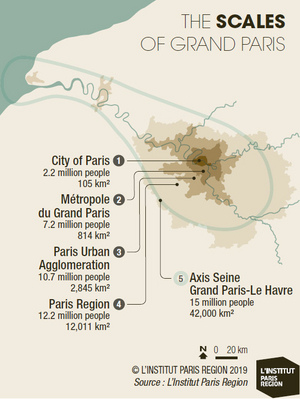

Compared to other large world cities, the Paris Region, in the heart of Europe, is exceptionally accessible, offers enviable quality of life, has a diversified and creative economy, and boasts unique cultural and educational assets. Somewhat compact, dense and diverse, Grand Paris is well known for its high quality public realm that makes it quite a “walkable” city. The fact that the Region is fragmented by transport infrastructures is, however, a handicap. Like New York and London, but to a lesser degree, Paris suffers from sharp socio-economic imbalances and social inequalities are acute, with a contrast between the prosperous southwest and the northeast, where there is a higher concentration of poor people and recent migrants. The number of homeless people is on the increase. Underprivileged areas are, however, relatively small and the level of inequality across the Region is considerably reduced by social benefits. Aware that the division of the Paris Region into so many different administrative areas, each with its own council, might adversely affect the implementation of the Grand Paris project, on 1 January 2016 the government enacted a law obliging local councils in the core area to group together within the Métropole du Grand Paris, a public inter-council cooperation body comprising the Paris Council and 130 councils in the surrounding area. The complex institutional system of the capital region (comprising the Paris Council, the suburban town councils, the Départements, the Grand Paris Metropolitan Council, the Île-de-France/Paris Region Regional Council, and the State) highlights the fact that metropolitan strategies necessarily involve a large number of players and take place on a range of different scales. There is no unified vision of the Region, but strategies, programmes and initiatives reveal a metropolitan project based on the (sometimes competitive) convergence of intense political energies and ambitions. The Métropole du Grand Paris is in charge of running a project for the central area. The Regional Council is tasked with economic and territorial development ensuring a balance between the core area of intense metropolitan growth and the outlying areas. The State underwrites ambitions for the capital as the cultural and economic heart of France, and ensures that its climate and energy commitments are met. Along with local authorities, stakeholders and residents, these bodies will have to answer certain fundamental questions by 2050. Standing as it does at the crossroads of these ambitions, the (Wider) Grand Paris project still lacks a democratic dimension: further involvement of citizens in the process would be an essential success factor.

(Wider) Grand Paris 2050: subjects of debate

Suburban growth has slowed over the past fifteen years: consumption of greenfield land is at its lowest historic level, and construction dynamics focus on brownfield recycling. According to the latest forecasts, the population of the Île-de-France region is set to rise to around;13.3 million by 2035, about 1.1 million higher than today. The Region will have to provide these people with diversified employment, affordable housing and efficient transport. Public opinion is increasingly sensitive to encroachment on farmland and nature areas, as opposition to the Saclay and Triangle de Gonesse urban projects has shown. A clearer strategy for the Green Belt would give the city’s outlying areas a new status. Reinforcing the urban green-blue grid will also be crucial in order to improve biodiversity, cool down the core area, and enhance quality of life by 2050. The principle of urban densification is still hotly debated, however: Paris seems to be allergic to the kind of vertical urban development seen in Shanghai, Istanbul or London. Extending the Paris model of urbanity to its outlying areas, to the detriment of industry and detached housing, calls for a shared vision. In the light of Brexit and on-going conflicts in Amsterdam, Barcelona and New York, the long-term impacts of major international investments, command functions, and mass tourism are also worth discussing. Beyond this, the “French passion”7 for equality between regions will continue to challenge the development of the Paris metropolitan region, which will take place to the detriment of its broader Region (the Paris Basin), other major cities, and the mythologised rural provinces. This means that the social metropolitan question in Paris—the acknowledgment of its role in welcoming new populations and its ability to offer satisfactory, fair living conditions to different categories of residents who drive the French economy—can only be approached within a national framework. Recognising the “quality of life for all” criteria when assessing attractiveness, and the ability of the capital of France to respond to the commitments of the Paris Agreement, encourage deeper thinking on mobility systems and economic models. Digital revolution and automation open new horizons in terms of work organisation and modes of consumption, which must be clarified. Changes in logistics could lead to congestion and pressure on agricultural areas in the absence of clear choices regarding the transition to a circular economy and green transport. Rethinking the future of the motorway network could be the first step, provided we think in parallel about the development of an intermodal mass transport system.

Léo Fauconnet, Political Scientist and Urbanist,

and Paul Lecroart, Senior Urbanist, L'Institut Paris Region

URBAN MOTORWAYS: FUTURE SHARED PUBLIC SPACES FOR GRAND PARIS?

This is, in summary, the question put to four multidisciplinary teams selected for the ambitious international competition on the future of roads in Grand Paris, launched in May 2018 by the Forum Métropolitain and its partners: the Paris Council, the Île-de-France/Paris Region Regional Council, the State, the Metropolitan Council, three county councils (départements) and eight administrative areas, with support from APUR and IAU (now L’Institut Paris Region). Exhibited to the public from June 2019 onwards, the teams’ proposals will fuel discussions on the future of the boulevard périphérique [Paris ring road] and initiatives to be put in place by 2030 and 2050 in order to optimise the use of motorways, integrate them more effectively, and reduce their impact on the environment, in the framework of a sustainable economic model. These approaches will be closely linked to the reinforcement of a multimodal transport system offering attractive alternatives to solo car use. The transformation of these infrastructures into ‘metropolitan avenues’ forms part of a global movement to reclaim the ‘car-oriented city’ of the twentieth century, as shown in studies by the Institut Paris Region on New York, Seoul, Vancouver and others*.

* Paul Lecroart, Reinventing Cities: From Urban Highway to Living Space, Urban Design Magazine, Issue #147, Summer 2018.

BLUE-SKY THINKING: INNOVATIVE PROJECTS FOR GRAND PARIS?

Since “Reinventing Paris” initiated by the Paris City Council in 2014, the principle of calls for innovative projects has spread like wildfire through the metropolitan region (“Inventing Grand Paris”), along the river (“Reinventing the Seine”) and as far as Vancouver and Auckland (C40’s “Reinventing Cities”), suggesting what a “(Much Larger) Grand Paris” might look like: 150 proposals have been made involving almost 250 hectares of land in 2018, and private investors have promised 7 billion euros to the Grand Paris Council. Beyond the financial optimisation of public sites by inviting the private sector to participate in their development and management, the idea is to imagine a city of tomorrow by bringing together investors, developers, architects, start-ups and users to find solutions to the ecological crisis and foster the emergence of a “sharing society”. These calls for projects spark enthusiastic involvement and fertile interactions leading to original projects… that will have to be brought to fruition. They take place in parallel with well established calls for projects for “Eco-Neighbourhoods” supported by the State and “Innovative and Sustainable Neighbourhoods” initiated by the Region.

They are also a legacy of the “Call for Metropolitan Initiatives” launched by Paris Métropole in 2010 following the Institut Paris Region workshops on the German IBAs (Internationale Bauausstellung or international architecture exhibitions). Unlike the IBAs, however, each site involved in a call for innovative projects tends to act alone, and struggles to fit into a strategic vision that remains to be formulated. As IBAs develop in France, the magic formula of a project process that draws from public debate, connects the region, and builds local and regional solidarity, still remains to be invented.

1. Translator’s note: “Grand Paris” means Greater Paris; “grand pari” means “great challenge”.

2. Now Forum métropolitain du Grand Paris, it groups 200 local authorities, including the Regional Council and Paris.

3. Translator’s note: “le grand huit” means “the rollercoaster” (literally “the big figure-of-eight”).

4. 3,300 hectares of urban projects, Observatoire des quartiers de gare du Grand Paris Express 2014-2017, Apur.

5. DRIEA Île-de-France, La construction de logements en Île-de-France, February 2019.

6. DRIEA and DRIHL Îdf, Apur, Insee, IAU îdF, Les conditions de logement en Île-de-France, 2017 (2013 survey).

7. Philippe Estèbe, L’égalité des territoires, une passion française, Puf, 2015.