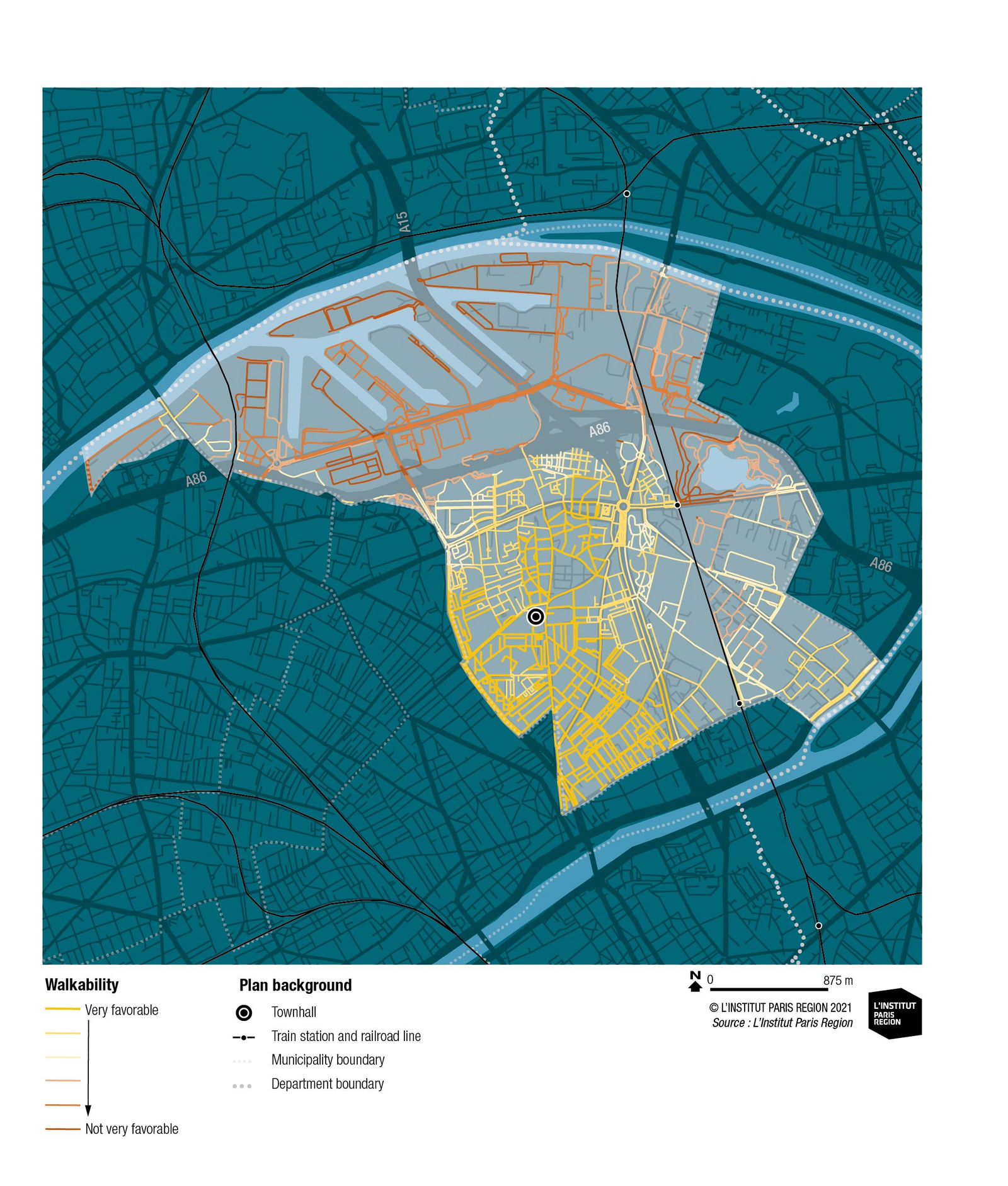

This commune is marked by its port and logistics activity, a neighborhood in the north of the city not very favorable to waling, and many urban cutoffs linked to the presence of road and rail rights-of-way. A city center around the townhall is suggested thanks to the presence of various businesses and facilities.

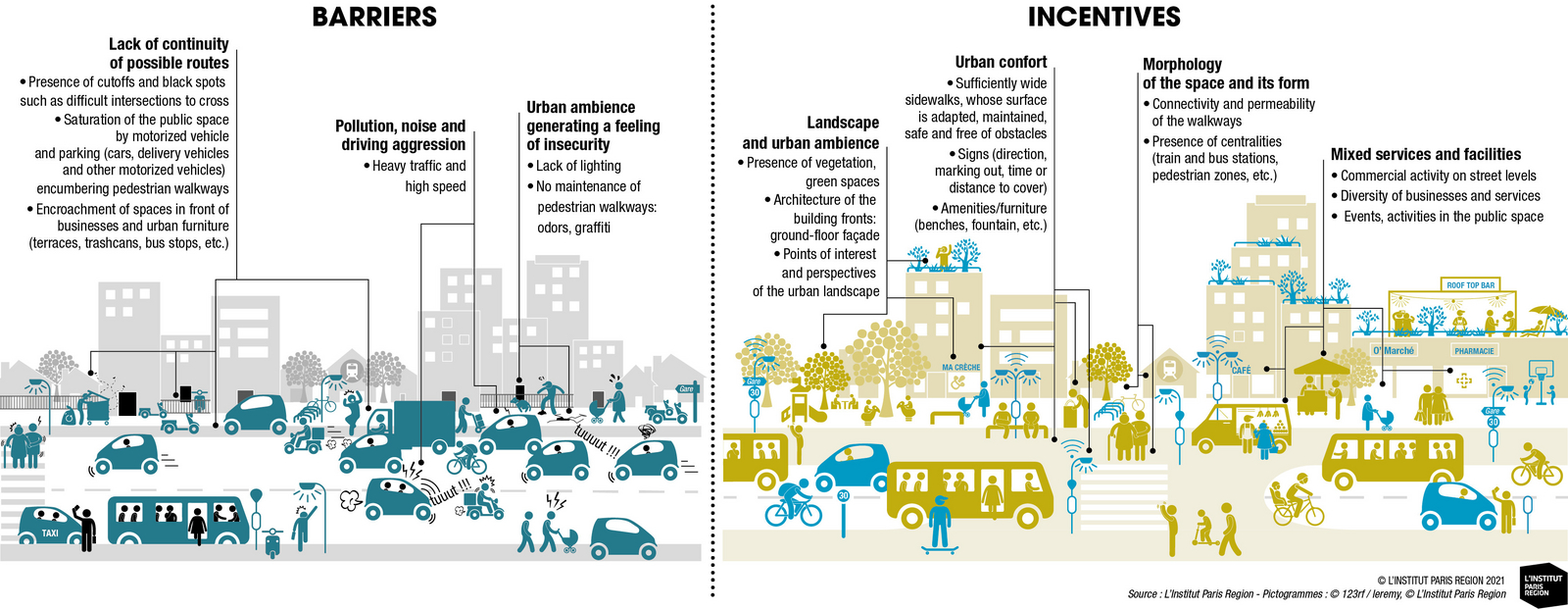

This index was built using the quantitative spatial characteristics currently available under SIGR6 having a positive or negative influence on walking in the city, such as the presence of sports, health or school facilities, local businesses and other amenities, but also urban heat islands or car traffic (via the number and width of roads). It could be enriched with the availability of new data. For example, those on urban comfort (notably the presence, width and surface of “sidewalks”) and those on urban furniture (foundations, benches, lighting, etc.). or on noise or street lighting, data unavailable on the regional scale. However, even while having all the quantitative elements on the public space, this index cannot describe the quality of the urban ambience: it fluctuates during the day, the seasons and from one individual to another, according to his or her gender, age, among other factors. The absence of noise and other disturbances in a space and the presence of amenities is not always enough to have the feeling of urban comfort emerge. Depending on individual criteria, this feeling is neither unanimous nor stable over time. It requires adapted survey and observation methods like those the Danish urbanist Jan Ghel has largely developed.