When civic techs facilitate democracy

Initiatives such as MaVoix, Démocratie ouverte, Parlement et Citoyens, Voxe.org are emerging in France as new digital tools of participation in political life. The so-called “Civic Techs” contribute to greater engagement by citizens, more participation in democratic life and the promotion of transparency by governments. As companions or instigators of radical change, Civic Techs herald a new era of governance.

Civic Techs play many roles, from supporting candidacies of citizens chosen by lot to stand in the 2017 parliamentary elections in France, to lending support to movements of protest or challenge of the established order and encouraging awareness-raising of various causes. Civic Techs and their role raise questions about what they are, the way they operate and the limits of their effectiveness.

Civic techs helping to renew action in the public arena

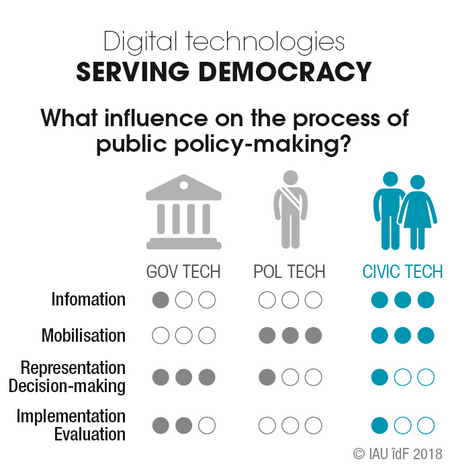

Reliance on digital technologies in politics is not new. As early as the election of Barack Obama in 2008, they were key to his election campaign based on the strategy of “community organising,”1 and are now very much part of public policymaking. After “Gov Techs” serving government institutions and “Pol Techs” serving political parties (where digital technology plays a more conventional role), Civic Techs are involved in public policy-making at four different levels:

- as sources of information on legislation, parliamentary activity, current controversies and political programmes. Civic Tech “Le Drenche” presents the pros and cons of political policymaking initiatives in order to help readers make up their minds. “Voxe.org” compares political programmes. “Nosdéputés.fr” and “Nossénateurs.org” monitor the activities of parliamentary representatives;

- by promoting rapid and massive mobilisation for a given cause, notably by on-line petitions (change.org, avaaz.org) or by the organisation of the prerequisites for militant action. “Nation Builder” defines itself as a “system working through communities” to serve NGOs, associations and political parties. This tool enables accurate profiling of members, collecting of gifts, mobilising of people in the field and instant communication by means of an integrated website;

- by developing numerous tools dedicated to representation and participation in decisionmaking. Of note here are “DemocracyOS”, experimentally used in Argentina, an open source platform (non-paying and independent) seeking to promote broad participation in political decision-making. “LaPrimaire.org” put forward a candidate chosen from an open citizen primary in the 2017 French presidential elections, based on a jointly constructed programme. “MaVoix” offers a service of random selection of volunteer citizens, who are then trained in how to devise proposals for legislation to be presented to electors for approval or not during a five-year mandate;

- inventing tools for the implementation and evaluation of decision-making processes. Civic Techs mine the availability of open data and the feedback from citizens in order to contribute to the analysis of the impact of public policy-making. “Etalab” is a Civic Tech dedicated to circulating information about government decisions or state organisations. “Open Data Soft” supports local authorities in the deployment of their strategies of data openness and enhanced availability of information.

Human mediation and traditional tools are still necessary

Even so, considering the “digital divide”, it is inconceivable that Open Techs alone can transform French political practice. However, Civic Techs can effectively incentivise citizens more generally to invest in many fields of public policy-making and its assessment but this does not resolve the problem raised by Daniel Gaxie in 1975 of the shortcomings of democracy due to people’s insufficient grasp of the issues2. People who are internet-disabled are still excluded, exactly as others are excluded from traditional modes of participation in public policy-making. Much supporting effort is needed to mobilise citizens, in particular those who are digitally disadvantaged. Significantly, the budget allocated to “participatory exercises” in Paris (for the second time early in 2017), twins access to an internet interface with a big presence of mediators to inform and help people to better understand the projects they are participating in. This signals that digital tools have a role somewhat limited to the support of a pre-existing conventional participatory approach. Digital tools have yet to overcome the barriers to mobilising the people most estranged from standard politics, the “invisibles” of society. Actual ability to “open up” democracy is still fairly limited. The risks of knowledge being inaccessible and of unfamiliarity with how to process it are real. How is produce this knowledge which is available thanks to digital technologies? Who screens the information? Information could be channelled and decision-making oriented by the makers of software or applications, even if the “entrepreneurs of digital democracy” (Stéphanie Wojcik) claim they have a certain ability to spread knowledge and power more equally (“horizontalization”). The open source dimension of software is also a divisive issue for those in the Civic Tech field. Some militate for free nonpaying availability of applications in the name of “digital common property”, fostering a virtuous circle, an open source software program being constantly improved openly and collectively. But others, the developers (or the software publishing houses they work for), are more in favour of recognition of property ownership and control. There is also the risk of ascribing exaggerated value to digital tools, because of people’s fascination with technology and a belief in technology’s power to offset citizens’ lack of involvement in civic action. The experience of those working in the Civic Tech field confirms that, to be really effective, human and technical mediations are interdependent.

Questions are also raised about the ability of these democratically innovative approaches to attain the legitimacy granted by existing universal suffrage election systems to the “anointed” representatives of “the people”. The problem of a system of representative democracy is how to take into consideration the existence of these new tools “for monitoring and influencing the decisions taken by governments in another way than by simply conferring a political mandate on the representative”. Undeniably, Civic Techs are beginning to play a bigger role in the digital environment, just as they are now part of the toolbox of political parties during election campaigns. But it is still too early to assess their impact on the actual participation of citizens in political life. No doubt “Civic Techs”, being means of exercising control over those in the public arena, they contribute, alongside other techniques, to enhance “democratic vigilance3”. By bringing citizens and elected officials into closer contact, Civic Techs ensure that user-friendly IT resources are brought into play so that the “citizen’s voice” is heard, and views expressed on choices affecting them. Through their ability to better monitor and influence public policy-making, “Civic Techs” are part of the process of building a revitalised model of democracy.

THE CASE OF MAKE.ORG

The Paris Region is committed to the Civic Techs. Thus, it recently teamed up with the campaign organized by the make.org platform to work out what action to take in the campaign against violence towards women. This campaign is taking place in three stages: first, an extensive consultation exercise on the social networks; second, formulating solutions; and third, implementing an action plan in close collaboration with the relevant associations. The platform has set itself the target of 500,000 sign-ups to its dedicated Facebook page, which was scheduled to come on stream at the end of November 2017. Thanks to these methods, along with its ability to link up with an extensive public, the make.org platform, like other Civic Techs, has the declared intention to invent new forms of citizen participation in public life because politics is not enough, as its slogan says.

Cécile Diguet, urbanist and Tanguy Le Goff, sociologist, L'Institut Paris Region

1. “During the 1930s, a factor of notable significance in the presidency of Franklin Roosevelt was the innovative use of radio; the election of John F. Kennedy in 1960 made extensive use of television and marketing techniques; the election of Barrack Obama in 2008 appears to have marked the entry of information and communication technologies, including more particularly the social media, into the world of political communication.” F. Heinderyckx, Obama 2008: digital turning point, Hermès, La Revue, 1/2011 (No. 59), p. 135-136.

2. Developed by Daniel Gaxie, the concept of “cens caché” (a play on “sens caché” or hidden meaning and “cens” as the census that puts people on the electoral roll) focuses on the ways in which citizens in a democratic system tend to self-exclude themselves from politics by reason of their feelings of social and cultural illegitimacy and of political incompetence arising from their low level of educational attainment. D. Gaxie, Le cens caché. Inégalités culturelles et ségrégations politiques (Cultural inequality and political segregation) Éditions du Seuil, Paris, 1978.

3. Ibid., id., note no. 2.

This page is linked to the following category :

Economy